This posts is a summary of the talk given by Deborah Stone for the LIS-Bibliometrics Conference 2022.

What is the idea of the nature of the thing that you’re trying to count? Categories are human decisions. Once you decide what belongs in the category you counting, you predetermine the number you’ll find. This is why every number is just a snake eating it’s tail.

Three points:

- A number reflects human decisions about what is important. What are the important qualities of a thing that make it belong to a category and therefore count?

- The crucial fact about a number is not how big or how small it is. It is about who counted. Who decided what counts?

- Counting is a form of power. It is the power to decide what matters.

Humans create numbers. Then they claim that their creations are independent of their own subjective judgements. Numbers are no more objective than words.

If we know numbers aren’t objective: Why do we use them anyway to guide important decisions?

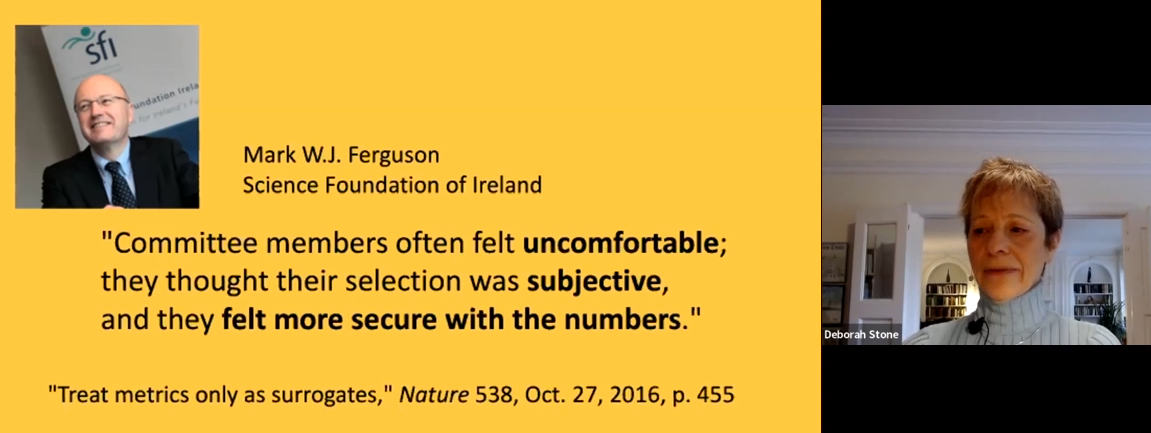

People want to use numbers, however crude they are, because we fear that the officials who have power over us, might be biased or play favourites. By setting firm, objective criteria to constrain them, we hope to reduce whim, favouritism, and prejudice. We call for numbers to protect ourselves from arbitrary power. Thats why so many institutions that evaluate programmes and people are increasingly using metrics instead of human judges, to promote fairness. Or so the argument goes.

Evaluation by numbers is supposed to make the people being evaluated feel that they are being treated objectively and fairly. Numbers make human judges feel more confident in their judgement. They rather hide behind the numbers.

Once we entrust ourselves to numbers, the snake is eating us, not its own tail.

People have long realised that numbers aren’t the objective gods that we’d like to believe.

Before we think about alternatives measures of impact. What are the hidden impacts of journals, articles and other research outputs that bibliometrics don’t measure?

The JIF as an evaluation tool creates pressures to conformity and discourages creativity. Citation serves as a mechanism for maintaining hierarchy in the profession. Journals with low JIF scores can still have a huge impact on scientific progress.

How might we better evaluate the impact of research and publications?

- The people affected by a policy should have a say in it’s development

- Ask people to tell me about a time you felt successful in their work? The answers tell us what people most care about and what their values are.

- Tease out the impacts from respondents words. What is grabbing? Use this as data.

- Ask yourself whether the meanings of impact you discovered can be broken down into countable units. What would that unit be? Would different observers agree?

If you must quantify, don’t rely on one unit like citations, build a multi-factor indicator.

Don’t rely exclusively on numbers. Stories are more compelling than numbers and allow space for personal discretion in evaluation decisions.

- People who count have biases too. They make subjective judgement in order to count. They exercise their biases when they decide what counts. Numbers only hide those judgments and biases and make them invisible. They do not eliminate them. Metrics are more efficient, but when you’re playing with individual’s careers, you owe them individual consideration. If you want to encourage originality and creativity, you need to allow for personal judgement. To reduce prejudice, use multiple evaluators. Insist that they engage in an open discussion about the thinking behind their judgments, preferably face to face.

Bibliometrics is both a commercial industry and a device for maintaining the status-quo hierarchy of knowledge producers. But if enough will practice these methods we can create a parallel universe in which evaluators and evaluated feel more honest, appreciated and effective.

More information

- ‘Counting: How We Use Numbers to Decide What Matters’ book by Deborah Stone

- The second gap found by the UNESCO OS Outlook is that monitoring efforts have mainly focused on scientific outputs (primarily in scientific publications, and secondly on datasets, software and hardware), but much less on OS processes, outcomes or values.

- Quality is Key

- Careful what you measure

- Measuring Community Health